Consider Yourself One of Us: Welcoming Audiences Who Are New to the Arts

“I've learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

― Maya Angelou

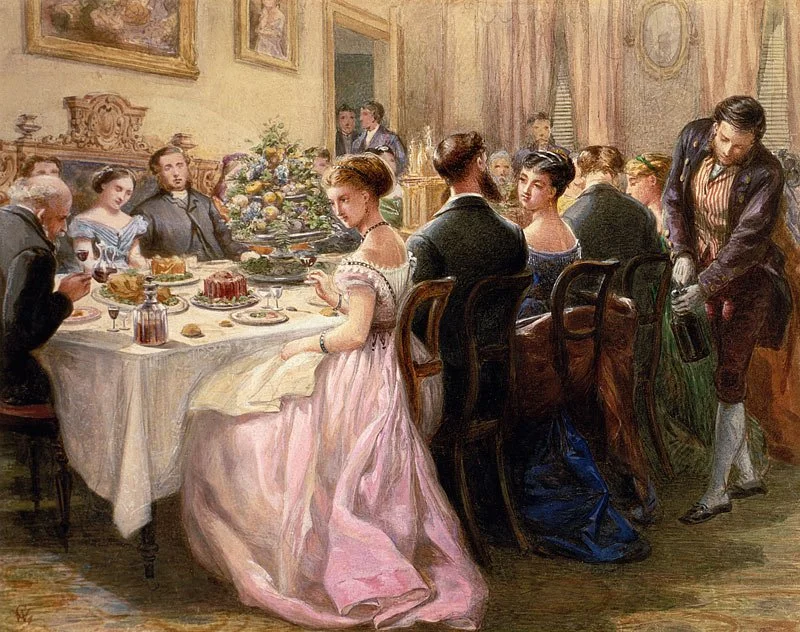

Imagine you’ve been invited to a dinner party. You’ve heard about the hosts but don’t know them well. You probably won’t know any of the other guests; in fact, this is a crowd you’ve never socialized with before. You’re not sure what to wear, how to act, or what’s expected; but for whatever reason, you’re curious and want to check it out.

Sound like an anxiety attack waiting to happen? Wait, it gets worse.

You can’t find parking, so you end up down the street, walking in the heat to where you think the home is. You walk in and nobody acknowledges you. When dinner is served, you take a seat, only to be told seating is assigned and you’re in the wrong one. The food arrives, and you dig in, but realize no one else is eating yet. You awkwardly put down your fork and wait.

The food is amazing; flavors you’ve never had, but surprisingly exciting. You want to express your delight, so you say, “This is really delicious!” Half the table glares at you. A few people shush you. The rest of the night is more of the same: guessing the rules, getting it wrong, feeling humiliated. You leave embarrassed, angry, and certain of one thing: you’re never going to a dinner party like that again.

If that sounds like your worst nightmare, you’re not alone. Unfortunately, it’s also how many arts organizations still treat new audiences. We expect them to know the unwritten rules. We shame them when they stray from our norms. We make it hard to enjoy the art unless they can crack the code of doing it the “right” way. It’s no wonder that their first visit becomes their last visit, and that they tell their friends not to go because, although the performance or exhibition was really engaging, it seems like they don’t want “people like us” there.

When we talk about developing new audiences, we’re really talking about the long-term sustainability, not just of our own organizations, but of the art form itself. This is existential stuff. That’s why there’s so much urgency around attracting new audiences. But getting them in the door is only the first step. We also have to rethink how we welcome them, how we help them feel like they belong, and how we invite them to connect. That means helping them understand how to engage with the work and giving them the freedom to respond to it in ways that feel honest and natural to them.

We’ve All Done It: Haunted by My Heart of Stone

I have to be honest: I haven’t always been great at making new people feel welcome in the arts myself. There’s a line where someone’s lack of etiquette can disrupt the experience for others. A couple of years ago, I was at a performance of the national tour of Six. Directly behind me sat a dad and his daughter, maybe 10 years old, who clearly knew the show backwards and forwards. She was thrilled to be there, singing along loudly with her favorite songs.

Of course, I had paid to hear the professionals, and the off-key chirping behind me was more than a little distracting. And not just because of the age-inappropriate lyrics she belted out (“All you wanna do, baby, is please me, squeeze me, birds and the bees me…”). She was breaking one of the two cardinal rules of the theatre (Jeopardy Answer: The first cardinal rule of the theatre. Question: What is don’t unwrap hard candies during the performance?).

So, what did I do? I turned around and glared at the dad… nothing. Then I locked eyes with the girl and gave her a firm head shake… still nothing. Finally, I leaned in and shushed her, sharper than I meant to. It wasn’t gentle. It was a clear reprimand, and it worked. She stopped.

Now, I could enjoy the performance fully. But what about the girl who was getting a huge thrill from seeing a show she clearly loves? I have no doubt that I ruined the experience for her. I’m sure she left the theatre feeling attacked and embarrassed because I corrected her behavior. It was a brief moment in my life, but it still haunts me. I passionately love musical theatre; it has brought me more joy than maybe any other pastime or form of entertainment. I want it to be around forever, and I want a new generation of young theatre-goers to be the patrons and supporters of the future. That’s not going to happen if we all treat young audiences the way I did that night.

But this article isn’t about scolding audience members for speaking up or protecting their own experience. It’s about encouraging arts leaders to take that burden off the audience. We should be the ones actively welcoming, embracing, and orienting new patrons so it’s not left to fellow guests to awkwardly correct them when something goes off-script.

Unfiltered Delight

Most artists love the instant gratification of hearing an audience enjoy their work. In a past life, I was a professional actor, working full time with a theatre company in Arizona called Childsplay, which tours shows to schools and brings kids to the theatre on field trips. Some of my favorite audiences were from schools for Deaf students. Because they couldn’t hear themselves reacting, they were completely unfiltered in expressing how they felt—positive or negative. You always knew where you stood. And if they were having fun, it was noisy. It was always magical. We could hear and feel how much they enjoyed what we were doing on that stage, “rules” be damned.

A Warm Hug at the Door

There are plenty of ways an organization can embrace the newbies. First: Orient them. Help them understand what they need to know to enjoy the experience, not just by handing them something to read. Make sure your staff and volunteers are ready to engage: answer questions, set expectations, and explain any hard-and-fast rules before it’s too late. (A pre-curtain reminder to silence your phone is important, but wildly insufficient.)

Second: Lighten up. Newcomers are going to make mistakes, either because they’re caught up in the moment or because they’re tuning out. Instead of scolding them, find ways to invite them in. If a rule matters, explain why, not just what. And if the worst thing that happens is someone claps at the “wrong” time during a symphony? Maybe take that as a win. They’re engaged. They’re moved. Let’s celebrate that and move on.

🔥 Hot Tip:

There’s a setting on your Apple Watch literally called Theatre Mode. It keeps your screen from lighting up and distracting the performers and the people around you during the show.

Leading by Example

Okay, I’ve harped enough about what we’re doing wrong. I’d love to share some examples of arts organizations who are finding ways to make new audiences feel welcome and to better enjoy their experience.

Speed Art Museum

At the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, the visitor experience has been getting a thoughtful overhaul—reflected not just in the gallery layout, but in how the museum talks about its role as a welcoming space. Director Raphaela Platow recently wrote about how the museum is rethinking everything from how art is grouped to how people are welcomed. Gone are the traditional categories by geography or timeline. Instead, they’re installing galleries around big themes that help people connect, reflect, and explore, not just absorb. A new “mirror/window/door” approach encourages visitors to see themselves in the art, glimpse new perspectives, and walk away changed.

But it’s not just the art that’s being reimagined, it’s the entire atmosphere. The team at Speed has clearly considered how first-time visitors often walk through the doors unsure of how they’re supposed to behave. Should I whisper? Can I laugh? Is it okay if I skip a gallery? Instead of posting more rules, they’ve made the space physically and emotionally more comfortable, adding cozy, living-room-style seating and low-key “chat spots” where docents invite conversation. Throughout the galleries, you’ll find journaling prompts and open-ended questions designed to spark curiosity and personal meaning, not test your art history knowledge.

It’s not about dumbing things down. It’s about removing barriers. Especially for people who don’t yet feel like museum people. The message is clear: you belong here.

Portland Symphony Orchestra

At the Portland Symphony Orchestra in Maine, the welcome starts before you even walk through the doors. Their First Timer’s Guide (easy to find in their website’s “Your Visit” section) speaks directly to the quiet anxieties that keep people away: what to wear, when to clap, how early to arrive. One of the best lines is simple but meaningful:

“If you feel particularly moved after a certain soloist performance or movement and would like to show your appreciation and clap between movements, go ahead! You may be the only one, but don’t hold in a natural emotional response on our account.”

And because not everyone’s going to do the reading assignment ahead of time, the orientation continues on site. Before many Classical concerts, Portland offers a free, 30-minute pre-concert talk in the hall itself, which, according to the orchestra, usually runs an hour before showtime. These are optional, easy to join, and designed to help audiences understand the music they’re about to hear. It’s a gentle, low-stakes way to help new patrons settle in, take a breath, and enjoy the show without worrying if they’re “doing it wrong.” The message here is clear: we’re glad you’re here, and we’re going to help you enjoy it.

To be clear, these aren’t the only organizations going out of their way to welcome new visitors with a warm embrace. But we can all do better. We can all do more.

Life of the Party

Maybe the disaster dinner party ruined all parties for you, and you’ll never go to another. Or—just maybe—there’s a better kind of party. One where the hosts and guests bring you into the community and don’t judge you for bringing your own experiences to the table. One where your presence is welcomed and your feedback is valued. And if that host serves a delicious, memorable meal on top of it all? You’ll come back every chance you get, just like you would to an art form that excites you and makes you feel welcome.

Jeff Goodman is a nonprofit consultant specializing in helping arts organizations clarify their mission and amplify their impact. A former professional actor, he brings a creative approach to his consulting, enabling organizations to tell compelling stories that resonate with audiences and build lasting support. His signature program, Mission Critical, emphasizes collaboration and is dedicated to making the arts accessible, engaging, and exciting for all.

Top Image: Shepard Fairey mural of Maya Angelou. Photo by Jonathan Furlong, via Obey Giant.